An Interactive Guide to the Bivariate Gaussian Distribution

Introduction

It’s not long after working with the normal distribution in one dimension that you realize you need to start working with vectors and matrices. Data rarely comes in isolation and we need more statistical tools to work with multiple variables at a time. The bivariate Gaussian distribution is normally the first step into adding more dimensions, and the intuition that one builds from the 2D case is useful in higher dimensions with the multivariate Gaussian.

I use “bivariate Gaussian” and “bivariate Normal” distribution interchangeably, sometimes “2d Normal”. These all mean the same thing.

Density of the Bivariate Normal

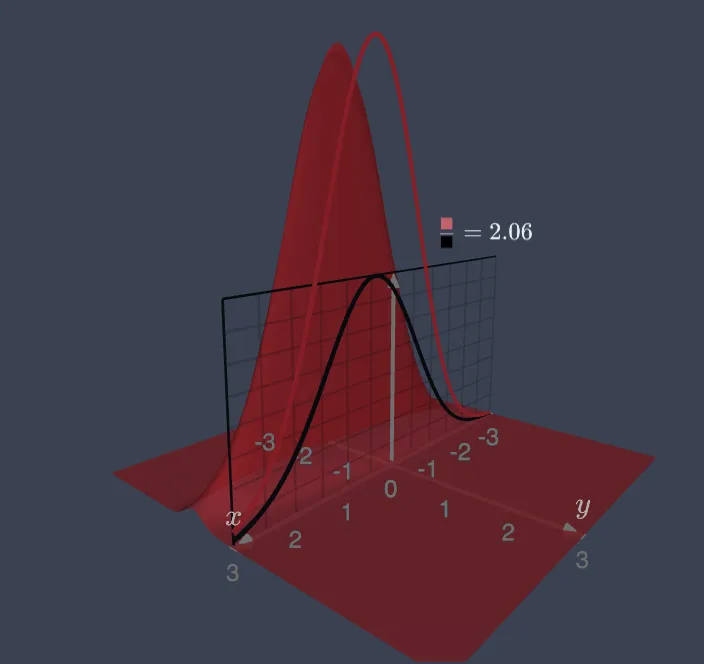

It’s a magical mathematical bump. It was a bump in 1 dimension and it’s still just a symmetric bump in 2 dimensions. The difference now is that there are more shapes that this hill can have because there’s more room to breathe in 3 dimensions! At first glance, there’s nothing glamourous about this function but it hides a lot of mathematical beauty.

Recall that the 1d Gaussian distribution has pdf:

where controlled the width of the distribution while controlled the location.

The story is similar with the bivariate normal distribution, which is defined with 5 parameters, manage the mean of the distribution while manage the covariance of the distribution. We say that the pair of random variables are jointly distributed as a bivariate normal distribution.

If you examine the density function, you can pick out the parts that that it shares with the 1d Gaussian. The interesting parts of this distribution lie in the the new parameter , which is the correlation between the two variables, and controls how much one variable moves with the other.

Here are some things to notice as you play with the function above:

- The maximum and center of mass of the density is at .

- The mean parameters can move around independently of the overall shape of the density.

- , and . The density function becomes degenerate when you get to the edges of this range. (I limit this range, but hopefully just enough to still get the sense of what happens if you push them to the extremes. Don’t break my applet!)

- The contours of this function, no matter the values of the parameters are elliptical.

- When , the density is symmetric about the and axes.

- When , the density seems to form a ridge along a positively sloped line, and when it’s along a line of negative slope. Slopes look symmetric along this line. This ridge line is the major axis of the contour ellipses.

- The ridge line is closer to the -axis when , and closer to the -axis when .

- When , as ranges from -1 to 1, the ridge line can range from to (from the -axis). When the ratio of to is more extreme, the power of to change the slope of the ridge line is much more limited.

You should get the sense that the density of the bivariate normal is fundamentally about ellipses. It’s ellipses all the way down! This is not a coincidence — the shape of that ellipse is entirely controlled by the covariance matrix.

If we rewrite the density function in vector/matrix terms so that the covariance matrix shows up explicitly, we get:

where and

The kernel of the function is , and has a special name. It is the Mahalonobis distance (squared) between and the bivariate normal distribution, and the function responsible for the elliptical contours.

The Covariance Ellipse

The primary components of drawing an ellipse are the center, and two diameters. One for the major axis and one for the minor axis. The major axis goes through the center and is the longest line you can draw, the minor axis is perpendicular to that, also through the center. The covariance matrix has all the information you need to draw the ellipse if you make the center of the ellipse at . The radii are the square roots of the eigenvalues of . The eigenvectors of give the directions of the major and minor axes.

Eigen- details

The details for this are no more than a standard 2x2 eigenproblem, and there are some simple formulas that we can use to get the eigenvalues and eigenvectors in this context.

If we label , with , then the characteristic polynomial is

Since is the trace of (or , the mean of the variances) and is the determinant of , we can write this as

For a single eigenvector , we examine the equation

which implies that both and . Since the matrix is singular, we only need to solve one of these equations because the other equation is some constant multiple of the first. A simple solution to the first equation is simply letting and , (since represents two eigenvalues, the other eigenvector will use the other eigenvalue). This will work unless . In that case, we can solve the second equation by letting and . If both and are 0, then the matrix is diagonal and our eigenvectors are .

Since in our covariance matrix, we just have 2 cases. That is, our eigenvectors are

may switch in the latter case depending on if for the eigenvector to match the respective eigenvalue.

The angle for the major axis is , where atan2 is a modified function to ensure the angle is always from the positive x-axis.

Conditional Distribution

The bivariate distribution has many beautiful symmetries, and I think they are highlighted well by the conditional distribution. The formula for the conditional distribution is a little more complicated at first but I think the picture and mental model is much more intuitive. Given that are jointly bivariate normal, the conditional distribution is interpreted as “I know the value of to be , what is the variability and probability distribution left in the random variable .” Since these random variables had a joint distribution, knowing the value of one of them should influence the information I know about the other one.

If I know that , I’m thinking about slicing my density function along the plane of . Once I take the slice, we will need a scaling factor in order to make sure the slice integrates to 1 for a valid probability distribution.

Here are some things to notice:

- The conditional distribution is a 1d Gaussian distribution.

- When , there are no terms that depend on or with a subscript of . In fact, it reduces to the marginal distribution of , which implies the random variables are statistically independent!

- The conditional mean is a function of only when . Since controls the “shearness” of the ellipse, the conditional mean shifts more when is larger.

- Even when , the conditional variance is not affected by .

Conditional Formulas

The most straight forward way to derive the conditional distribution formulas for a bivariate normal distribution is to use the definition of conditional probability (and some patient algebra):

The marginal distribution of is a 1d Gaussian distribution, with mean and variance . This result is presented later in this blog post, but is often used to define the bivariate Gaussian distribution in some textbooks — any linear combination of the variables is also normally distributed.

We’ll work with the constant term and the things inside the exponential term separately. The constant simplifies:

Since in a normal distribution, the variance shows up in the constant term, we get a hint of what the conditional variance will be, .

The exponential term simplifies to:

In total, if we combine the constant term and the exponential term,

we get the pdf of the conditional distribution with mean and variance :

Regression Perspective

There is an intimate relationship between conditional distributions and regression. Suppose we are in a simple linear regression scenario regressing on . We can interpret as the population slope of the best fit line. Remember that together change the major axis of the ellipse, and thus the main direction of the relationship for these two variables. In order to see the resemblance of the formula, notice:

The slope of regression can be pulled out from the covariance matrix directly, if we label then . If we substitute with the sample version, we get

This is the formula for the slope estimate in the simple linear regression of assuming normal errors. Written in this manner,

we have a very intercept plus slope like interpretation that the conditional mean will shift based on best fit regression line, depending on how far shifted we are from the center of the bivariate distribution.

Note that the slope of this regression line is not the same as the major-axis line of the covariance ellipse that runs through the bulk of the bivariate distribution. Even though they trend in roughly the same direction, they represent different concepts.

The short explanation of why these are different is that the major axis line is the direction of the eigenvector, which deals with distances from points directly to the line, perpendicular, whereas the regression lines deal strictly in vertical or horizontal distances between points and the line, depending on if we regress y ~ x or x ~y.

Marginal Distribution

The marginal distribution is trying to disregard one of the variables altogether. If I average out all the variability across the dimension I don’t care about, what is the probability that is left? The mental model I have for marginals is to integrate out one of the dimensions so that the density is all “squished” into the dimension I care about.

Some things to notice:

- Only 2/5 of the parameters determine the marginal distribution. is left out of both marginal distributions in the x and y directions.

- In the bivariate normal, you can either think about the “squishing into 1 dimension” as a projection of the density into that dimensions, and then scaling the distribution appropriately so that everything adds up to 1. Or you can think about is as truly summing up everything in the excess dimensions and integrating. I’ve added a button so that you can see these different perspectives.

- The location of the 1d grid is somewhat arbitrary. It doesn’t need to be at , we’re just integrating out the entire dimension.

Integrating in 2d vs 1d

Plotting the 2d Gaussian next to the 1d Gaussian makes me appreciate some subtleties of measure theory. If you have low variance, and an extreme value of , you can make the 2d density appear MUCH larger than its 1d marginal distribution, and yet, the area under both of them is ALWAYS 1. This was quite shocking for me to see at first! Integrating, the density will actually appear to shrink. The half-rationale for this is that the integration is happening over the 2 dimensional space vs a 1 dimensional space (against lesbegue measure in vs ), which are totally different. A point in 2d space is technically holding less “weight” than its 1d counterpart, a “point” in 1d is holding the weight of the entire real line perpendicular to it when calculating the integration. Before seeing these animations, I always thought the marginal distribution of the bivariate normal was straight forward and “made sense”, but now I’m more impressed that more terms like rho don’t appear in the marginal distributions. Although measure theory was designed as an extension of geometric concepts like area and volume, I think of it as more an algebraic discipline since physical intuitions can often fall apart, e.g. Banach-Tarski paradox.